Well I do have some limited knowledge of making sprites and I do like the suggestion you made, I'm just slightly concerned the size of the sprite will be too small but one can increase the size of the pixels and all...I will check it out better.Well I'm a bit embrarassed to admit to know this, but I think that there could be something of a solution to this.

O.K., here goes... Micro-Heroes. Oh boy. I've just admitted to knowing about these things. I've admitted to the world - which is this Forum - my childish nature. All you need is MS Paint - and make sure that the images are gif.

Anyway, for those of you that don't know, Micro-Heroes are used by the artistically challenged to create or give a visual representation of characters that are either part of pop culture, or of original provinence. I've seen a lot of Super-heroes and fan made heroes (and some other, more indecent imagery which I will not elaborate on).

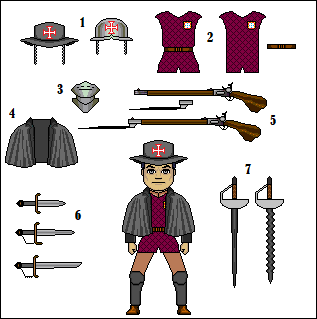

Anyway, a while back, I decided to use the Micro-Heroes to create my own version of the Osprey books, specifically, Man-At-Arms and Warrior. I was going to post it in Alternate History Maps and Graphics, and I was going to call it Kestrel Military History books or some such nonsense. Here's an example:

View attachment 862914

Pretty childish, isn't it? By the way, this is supposed to represent a Portuguese soldier in an alternate timeline in which Portugal didn't mess up. I even made an attempt at alternate guns and all, done in the good ol' Osprey style.

If this does interest you for visual representation of what you want to see, Micro-Hero templates can be found by using Google although I haven't checked this stuff out in some time.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Cessa o Nevoeiro: O Surgir do Quinto Império - A Portuguese Timeline

- Thread starter RedAquilla

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 62 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

The Great Religious War: The Netherlands and the Americas The Great Religious War: The Iberian Peninsula Polish-Swedish War Part 4 Europe: Between 1625 and 1628 The King's Death: An Appraisal King Filipe's First Year: The Pompous Year Europe: The Polish-Lithuanian Campaign The Kingdom: Political Developments of the 1630s

Europe: The Polish-Lithuanian Campaign

The Polish-Lithuanian Campaign

A Campanha Polaco-Lituana

A Campanha Polaco-Lituana

Just as the Portuguese troops were about to leave for Guedanhesque, the sick and mad Duke Teodózio II de Bragansa abdicated his position as Condestável de Portugal in favour of his eldest son and heir João Sebastião de Bragansa, Duke de Barselos. While this was still a consequence of Duarte II’s agreement with João I de Bragansa in 1580, João Sebastião was considered an able commander despite his young age and had gained experience while fighting the Huguenots in 1625.

There weren’t, however, many able commanders that could be more worthy than João Sebastião, however, his uncle Duarte, Marquis of Montemor-o-Novo died on May 28, 1627, and he was likely the best option if he had been alive; Fransisco da Gama, Marquis of Niza was another good option but his experience with Overseas affairs made him more valuable on the Conselho do Ultramar, not to mention he was old and did not want to go to Polónia-Lituânia.

The Portuguese forces were organized in three Tersos, each had the usual hierarchy with the Mestre-de-Campo [Master-of-the Field/General] at the top but for this expedition, the Condestável was above the Mestre-de-Campo rather than accumulating both positions as it had been until then. Some argue that it was because João Sebastião was still young and thus the Tersos were led by more experienced men, others said it was to better coordinate the troops and some say it was to emulate the Atamano [Hetman] position of Polónia-Lituânia as both positions had now the same responsibilities and thus a consequence of the military exchanges between both countries.

Filipe I introduced a change in his Tersos, namely, he wanted to name them like the Roman Legions rather than following the Spanish model of naming their place of origin because the troops that made the Tersos Reais [Royal Tercios] were from different parts of the country. He chose to name the Tersos according to the Zodiac so the Terso Real Nº1 became the Terso I Leão/Leo, Terso Real Nº2 became Terso II Jémeos/Gemini and the volunteer Terso became Terso III Caranguejo/Cancer. It was also clear from this decision that Filipe wanted to create at least 12 Tersos.

The Mestre-de-Campos were the following:

Name | Commander |

Terso I Leão | Luíz de Ataíde, Marquis de Santarém |

Terso II Jémeos | Luíz de Noronha e Menezes |

Terso III Caranguejo | Fransisco de Melo |

Ataíde was a very experienced man with good relations with Prince Ladislaus, had served as Ambassador to Polónia-Lituânia and had some knowledge of Polish. Luíz de Menezes was the younger brother of the Duke of Vila Real, less headstrong and just as experienced as he served in King Henrique’s War (1595-1597) and against the Ottomans (1618-1620). Fransisco de Melo, a cousin of the Marquis of Ferreira did not have as much experience but he showed signs of being a good commander. Since the Polish-Lithuanians were focused on cavalry, the Portuguese did not send any.

A fleet of 12 ships took the troops to Polónia-Lituânia while the fleet harboured at Copenhaga escorted them to Polish harbours. The Swedish Navy more numerous tried to stop them but were beaten down in every engagement with minimum losses to the Portuguese who managed to break the Swedish Blockade and keep pressure on the occupied coast. Following this success, the Portuguese troops managed to disembark at Putsque [Puck] and the Polish Navy joined the Portuguese Navy.

During the winter of 1628-1629, most of the Polish and Swedish troops ceased fighting except around Brodenhitsa [Brodnica] where the Swedish were trapped and running out of food supplies though Axel Oxenstierna, Gustavo II’s Chancellor, managed to relieve the garrison and beat the Polish at the Battle of Gujeno [Górzno] which made the Seím [Sejm] increase the war budget and raise a theoretical army of 18 000 soldiers.

Gustavo was keen on preventing the Portuguese from joining the Polish forces so he led 9 000 soldiers (5 000 infantrymen and 4 000 cavalrymen) from Mariemburgo/Malborque [Marienburg/Malbork] in occupied Polish Prúsia to Polish Pomerânia where they blocked the Portuguese advance. João Sebastião de Bragansa had taken a longer path to avoid the Swedish forces but on June 22 he found the Swedish scouts on his way and with Conhiétspolsqui far away, a battle became inevitable.

Concerned with his situation, the Condestável sent riders to ask for support from Guedanhesque and Estanislau Conhiétspolsqui [Stanisław Koniecpolski]. The Polish Hetman had already dispatched 3 000 riders once he realized Gustavo’s plan but they would take time to reach the Portuguese. The city council of Guedanhesque debated answering the Portuguese plead and in the end, they decided on sending 2 000 troops which were not going to arrive in time.

Battle of Cartuze

João Sebastião decided to fortify his position south of the town of Cartuze [Kartuzy], knowing that if he kept moving he would be flanked or even surrounded. The Portuguese odds were not favourable from the start, they only had 8 000 men against 9 000, they had no cavalry while the Swedish had 4 000 reiters and they were using ship cannons to complement their lack of field artillery pieces.

The Portuguese needed to play their strengths, namely accuracy and discipline. The three Tersos were positioned in tight formations on the outskirts of the town with the veterans in the flanks and the volunteers in the centre, the local population was ordered to hide away. This positioning covered their rearguard because the Swedish cavalry would have to move inside the town’s tight streets which would slow them down and give enough time for the Portuguese to reposition. The two lanes of pikemen stood at the front inside trenches with the musketeers positioned behind them well covered and ready to aim.

Once he saw the Portuguese positioning at midday on June 23, Gustavo understood he was in for a battle of attrition. Despite knowing that Conhiétspolsqui was coming in his way, the Swedish King believed he could weaken the Portuguese Army before it could join the Polish and thus he sent his cavalry to soften the Portuguese with caracol manoeuvres which were met by a coordinated barrage of musket volleys that caused heavy casualties to the Swedish especially when the Portuguese were able to time their volley with the Swedish one.

Gustavo sent the few artillery pieces he had brought with him to bomb the Portuguese but they remained steadfast in their position and bombed him back with their improvised artillery. Deciding that charging the Portuguese position would end up in carnage to his forces, Gustavo decided to focus his forces on a single flank. He was unaware of João Sebastião’s decision to have his best troops in the flanks and thus he decided to attack the Portuguese’s left flank (Terso I Leão).

At 16:00, the Swedish artillery focused on the Portuguese right flank (Terso II Jémeos), the cavalry once again did a caracol attack but this time only on the centre and left flank to weaken them and the infantry started moving towards their designated goal amidst artillery fire. Half an hour later, the Swedish infantry was approaching the Terso I Leão and Ataíde ordered the musketeers and artillerymen to shift to fire at will.

The Swedish took heavy losses but their resolve did not falter and they still outnumbered the flank (4 000 vs 3 000) while their cavalry kept the Portuguese right flank and centre busy. Contrary to what they were used to, the Swedish troops found themselves against an opponent that stood their ground with determination but most importantly cohesion and discipline even when nearly all the Portuguese troops had never fought in a battle before and thus lacked experience in the field.

After an hour of vicious fighting, Luíz de Menezes and Fransisco de Melo saw an opportunity in the fact that the Swedish cavalry was keeping the bulk of their army busy while the Swedish infantry could not overcome the Terso I Leão and if they took a gamble and committed their entire forces against said infantry troops they could win the battle. Ever cautious, João Sebastião did not really want to leave his position but he too had seen the opportunity and decided to commit to it.

At 17:23 after another caracol attack, Menezes and Melo ordered their Tersos to leave positions and move, shouting ¡Santiago! and ¡São Jorje! rather than staying quiet as was usual at the time and by doing so combined with artillery barrages covering them, they surprised the Swedish cavalry and left it in jeopardy without space to reorganize itself.

The Swedish King soon saw the two Tersos rushing in an oblique formation to support their left flank and Gustavo saw the imminent encirclement of his infantry so he called for an evacuation of it and rushed to cover its rearguard. Unable to charge, the Swedish cavalry had to fight in a melee against pikemen and the most brutal phase of the battle began without heavy casualties from both sides with Gustavo being injured in the skirmishes. At last, João Sebastião wary of his losses eased the pressure on the Swedish which in turn allowed them to leave the battlefield.

The Swedish had between 3 000 to 4 000 casualties in the battle and lost 14 leather cannons, being the worst bloodbath the Swedish had suffered till then, while the Portuguese had lost about 3 000 making the victory almost a Pyrrhic victory with the upcoming Polish reinforcements saved them from such outcome. Neither side was happy with the outcome, João Sebastião felt he lost too many men and that he should have kept his defensive strategy despite recognizing that it would have made the battle last longer and perhaps lead to a defeat. The Portuguese commanders recognized the critical role that their improvised artillery had played and wanted more of it, which they did not get and were sure that the Polish Cavalry could relieve the pressure on their infantry in future engagements.

Gustavo was concerned that his troops were not yet ready to fight the Iberian and Imperial Tersos. For the first time, he fought a peer with a very strong infantry formation and he was concerned with how well it would work with the fearsome Polish Cavalry and if the Emperor had troops as strong that would beat his planned invasion of the Empire quickly so he knew that he had to be even more cautious than he had been. What he did know was that he had to negotiate likely from a worse position than before but if that didn’t work, forcing his opponents into costly sieges when they lacked artillery and only engaging when he had numerical and artillery superiority was the key to getting what he wanted.

The Portuguese were able to continue their march and meet Conhiétspolsqui who wanted to harass the retreating Swedish but was unable to due to the distance they had gained on his horsemen. After a military reunion with few incidents, Conhiétspolsqui gave full control of the infantry to João Sebastião while he remained in command of the cavalry. Because Fransisco Coutinho, Filipe I’s Prime-Minister was against sending more troops to fight in Prúsia and was pushing for a diplomatic victory after the victory at Cartuze, Bragansa had to complement his casualties with Polish and Cossack troops but these were limited to be pikemen as they were usually taller and stronger than the normal Portuguese soldier who because of his mandatory training was a far better shooter than them.

The rest of the Polish, Cossack and Nogai infantry were organized in four regiments, two of Polish troops, one of Cossacks and a smaller one with Nogais. In total, the Joint Army had a 15 000 strong infantry force. As for the cavalry forces they were raised to 4 000 once the Joint Army arrived at Culme [Chełmno]. The Joint Army then invaded the occupied Mariemburgo Province and forced Gustavo to flee as he was still injured from his previous battle and without enough men to battle but he left sizable garrisons in the main towns, including Mariemburgo which was defended by 1 000 Swedish troops.

The Portuguese and Polish commanders understood that they lacked the means to lay proper sieges, a problem that Conhiétspolsqui had long been aware of but was unable to do anything due to lack of funds in the previous years. As the Livónia front was stagnant because of the inability of Hetman Lev Sapiega [Lew Sapieha]’s troops to a thing due to their small number and political intrigues promoted by his main rival in Lituânia, Cristóvão Radevila [Krzysztof Radziwiłł], the Polish forces were limited in their actions.

Or so it seemed...Conhiétspolsqui emboldened by his larger and increasingly more efficient army and the struggle the Swedish endured in the previous winter proposed they bypass the fortified towns, pressured Gustavo into a battle and starved the garrisons, a strategy that the cautious João Sebastião only accepted because the Portuguese Navy at this point controlled the coast of Polónia despite the Swedish attempts to beat them away and his army swelled to 22 000 men with the arrival of more infantrymen that were organized a new regiment. This meant that while the Swedish were not fully trapped in Prúsia, supplying them was very difficult.

With the Joint Army entering into the Duchy of Prúsia, Gustavo tried to negotiate with the Polish nobility and with Filipe I himself as he knew that Sijismundo III would not accept ending the war without recovering Suésia. He got Fransa’s diplomatic support with Richelieu trying his best to make the Portuguese King end the war because Fransa needed Suésia to join the war against the Habsburgos and Inglaterra and the Provínsias Unidas were quick to join the effort to end a war that was economically problematic for them.

Filipe felt he still needed more victories but was also wary of continuing the war and Fransisco Coutinho who had been against the war from the very beginning pushed for peace negotiations but on Portuguese and Polish terms. By September 1629, Filipe sent his terms to Gustavo II and they were as follows:

- The end of the blockades of the Polish ports;

- The abandonment of all occupied territory in Polónia-Lituânia;

- A peace settlement of at least 10 years between Suésia and Polónia-Lituânia.

However, Gustavo felt that the abandonment of Polish-Lithuanian territory was a rather controversial point of contention because while he was willing to abandon Prúsia, he certainly would not abandon Estónia and Northern Livónia. Another problem with the negotiations was Sijismundo III’s obsession with recovering the Swedish throne which Gustavo could not accept and the Portuguese were not in the mood to pursue. The Seím’s position was in line with the Portuguese stance though they wanted monetary compensation and their interpretation of the territory that Suésia had to abandon was different than what the Portuguese were thinking.

In the field, the Joint Army was making progress and cornering the Swedish troops to the sea, pressuring Gustavo and worrying his foreign supporters that he could be in for a major defeat and together called for a peace conference between Portugal, Polónia-Lituânia and Suésia at Mariemburgo with the mediation of Fransa, Provínsias Unidas and Inglaterra-Escósia. The mediators argued that the Portuguese terms were fair and pushed for them to be implemented only stating that the borders between Polónia-Lituânia and Suésia should be those agreed at the Truce of Parnava [Parnawa], the last document signed by both sides.

These borders were agreed upon by all parties but Sijismundo remained stubborn in abandoning his claims to the Swedish throne and the negotiations stalled until all parties agreed to ignore that point of contention and the Treaty of Mariemburgo of October 17, 1629, was signed without any further land battles occurring. The Swedish troops were evacuated during the winter season to the borders agreed upon in the Truce of Parnava which they were committed to defend but the rest of the Polish settlements were returned and the Polish ports were fully open again and trade resumed fully by 1630.

Gustavo returned to Estocolmo [Stockholm] and immediately began preparing a campaign against the Empire, having taken substantial lessons from his latest war and was confident that he could beat the Imperial Tersos. Sijismundo was disappointed with the outcome of the war and with the Portuguese as he felt they didn’t want to help him as much as they promised but Polónia-Lituânia was able to return to peace which also meant that half the troops were dismissed to cut the military spending despite the King and the Hetmans' attempts to conserve as many trained troops as they could to make sure the army was capable of responding to the constant threats the country faced.

The Polish Navy was still thriving and none of their remaining ships had been sunk. Polish sailors and captains were able to get valuable experience while serving under the stronger Portuguese Navy, adopting their doctrines and Guedanhesque was no longer against an enlargement of the navy in fact, they were now Sijismundo’s biggest supporters in the endeavour because they believed a strong navy was crucial to prevent another situation such as the one they lived.

The Portuguese soldiers were received with pomp by Filipe I who while not fully happy with the performance, as he wanted to see his men win more battles and die less, was still proud of their victory and most of all, because they succeeded in all their objectives and thus they received a bonus payment. As Suésia’s performance was to surprise everyone in the following years and given that Portugal beat them in the only battle they thus far fought, the Portuguese Army gained a lot of prestige.

However, the Condestável and the other Portuguese commanders were not happy with the logistics of the Army or their lack of artillery. Furthermore, they had yet to test their cavalry forces in combat and they wanted to employ further reforms. Filipe I being obviously interested in improving the army gave the title of Minister of War to João Sebastião de Bragansa, tying the Ministry of War with the title of Condestável and giving all the means for his cousin to reform the Portuguese Army.

Filipe I also rewarded the commanders with titles, and thus he quickly broke away from his father’s policies in this regard. Fransisco de Melo was granted the title of Viscount of Asumar, Luíz de Ataíde, Marquis of Santarém was made Count of Moledo, João Sebastião was made Count of Alvarães and the County of Loulé was restored in the person of Luíz de Noronha e Menezes.

Perhaps the biggest rupture with his father’s title-giving policies was that he made Afonso de Portugal, the new Marquis of Valensa and Count of Vimiozo, Count of Freixiel. João IV never granted a title to a son of a newly deceased man he wished to reward arguing that the son was not the father but Filipe I did not follow this and rewarded the son of Luíz de Portugal, who died on November 10, 1629, for the man’s naval victories against Suésia.

João Sebastião de Bragansa came out of the war with much prestige and his fortune had now increased. As his father, Teodózio II was insane and with his health deteriorating, João Sebastião assumed full control of the Duchy of Bragansa’s destinies until Teodózio died on November 29, 1630. After a pompous funeral with Filipe I’s presence, João Sebastião became Duke João II de Bragansa, likely the most powerful noble in the entire Peninsula outside of Olivares and Fransisco Coutinho for obvious reasons.

Duke João II Sebastião de Bragansa, Condestável de Portugal (OTL João IV)

Had this one written a while back but was trying to both progress in the rewrites and make it more realistic. I think the Battle of Cartuze was realistic, reflecting your usual Portuguese lack of means, adaptability and unpredictability which caught Gustavo, who was also not used to fighting infantry on the same level as his, by surprise.

Next update will be about Filipe I's son's early years. I might put the nobility in it too because the two things are entangled. Also, I have decided to follow the decades set of chapters like in Vivam Lusos Valorosos so there will be a set of chapters about the 1630s, another about the 1640s and so on. I think this way I won't be stuck for months in European Wars.

Without further ado, thank you for sparing time reading and I hope everyone has a nice day and stays safe.

I love to see this historical account continuing. Sometimes I wish this thread was in the dedicated alien space bat section so that Portugal could be wanked further.

Anyhoo while you're writing your story, figuring out where it's going, I would like to add a few tidbits here and there which you may or may not decide to use

According to this article, in OTL weapons production in Portugal slowed down significantly following the restoration, which I can already see is not the case in your scenario. That being said, the name 'Lazarino' does seem to show up in my searches of Portuguese flintlocks, so maybe that name might appear in your timeline. And flintlocks made in Portugal seemed to have hammers (or cocks; or dogs) that were slightly different from the norm:

This comes from here, by the way.

Another little tid bit that may or may not be of use. I don't know how important the Goan gunsmiths will be in your timeline. Now, most sources I've read seem to say that the famed Japanese Tanegashimas are based off of Goan designs, and I assume that the Goans are still making guns like this in your timeline. I have come across an interesting Japanese website (I used Google translate extensively - not a good idea, but it was all I could do). Anyway, it showed an interesting conversion of the Tanegashima into a trapdoor breechloader:

(The Japanese call these shrimp butts by the way - not shrimp tails, shrimp butts; they're a localized version of a Wilson rifle - a type of rifle I have never heard of until finding this Japanese website)

If you decide that a Portuguese alchemist/pharmacist/witch will discover fulminates earlier in this timeline than in our own, and start using them in firearms (maybe taking that leap in making cartridges similar to the ones of the late nineteenth century which have the primer, powder, and bullet in one simple package), this could show how Portuguese guns might look. If you think it's plausible.

Besides, why not shrink a berço and make a berçete?

P.S. I'm curious how you're going to introduce bayonets to the army (the Chinese were using them in the fifteen hundreds), and for how long will the Portuguese be using Tercios. Will they come up with something of their own?

P.S.S.

I made this:

Supposed to be an eighteenth century Portuguese soldier from an alternate timeline, done in the style of Osprey military history. I did this just to show off my infantile nature.

I eagerly await the next chapter to your "Hestória do Reino e Império de Portugal - do reinado do D. Duarte II, até aos dias de hoje"

Anyhoo while you're writing your story, figuring out where it's going, I would like to add a few tidbits here and there which you may or may not decide to use

According to this article, in OTL weapons production in Portugal slowed down significantly following the restoration, which I can already see is not the case in your scenario. That being said, the name 'Lazarino' does seem to show up in my searches of Portuguese flintlocks, so maybe that name might appear in your timeline. And flintlocks made in Portugal seemed to have hammers (or cocks; or dogs) that were slightly different from the norm:

This comes from here, by the way.

Another little tid bit that may or may not be of use. I don't know how important the Goan gunsmiths will be in your timeline. Now, most sources I've read seem to say that the famed Japanese Tanegashimas are based off of Goan designs, and I assume that the Goans are still making guns like this in your timeline. I have come across an interesting Japanese website (I used Google translate extensively - not a good idea, but it was all I could do). Anyway, it showed an interesting conversion of the Tanegashima into a trapdoor breechloader:

(The Japanese call these shrimp butts by the way - not shrimp tails, shrimp butts; they're a localized version of a Wilson rifle - a type of rifle I have never heard of until finding this Japanese website)

If you decide that a Portuguese alchemist/pharmacist/witch will discover fulminates earlier in this timeline than in our own, and start using them in firearms (maybe taking that leap in making cartridges similar to the ones of the late nineteenth century which have the primer, powder, and bullet in one simple package), this could show how Portuguese guns might look. If you think it's plausible.

Besides, why not shrink a berço and make a berçete?

P.S. I'm curious how you're going to introduce bayonets to the army (the Chinese were using them in the fifteen hundreds), and for how long will the Portuguese be using Tercios. Will they come up with something of their own?

P.S.S.

I made this:

Supposed to be an eighteenth century Portuguese soldier from an alternate timeline, done in the style of Osprey military history. I did this just to show off my infantile nature.

I eagerly await the next chapter to your "Hestória do Reino e Império de Portugal - do reinado do D. Duarte II, até aos dias de hoje"

Last edited:

So in other words, this chapter wasn't realistic?I love to see this historical account continuing. Sometimes I wish this thread was in the dedicated alien space bat section so that Portugal could be wanked further.

I've read that article for my 19th Century timeline. That said, Portuguese production will not decrease, instead it will increase but I will address that in an Armed Forces chapter.Anyhoo while you're writing your story, figuring out where it's going, I would like to add a few tidbits here and there which you may or may not decide to use

According to this article, in OTL weapons production in Portugal slowed down significantly following the restoration, which I can already see is not the case in your scenario. That being said, the name 'Lazarino' does seem to show up in my searches of Portuguese flintlocks, so maybe that name might appear in your timeline. And flintlocks made in Portugal seemed to have hammers (or cocks; or dogs) that were slightly different from the norm:

Goa being the capital of the Estado da Índia and the second most important city in the Empire will continue producing weapons to sustain the Estado da Índia.This comes from here, by the way.

Another little tid bit that may or may not be of use. I don't know how important the Goan gunsmiths will be in your timeline. Now, most sources I've read seem to say that the famed Japanese Tanegashimas are based off of Goan designs, and I assume that the Goans are still making guns like this in your timeline. I have come across an interesting Japanese website (I used Google translate extensively - not a good idea, but it was all I could do). Anyway, it showed an interesting conversion of the Tanegashima into a trapdoor breechloader:

I can't tell if you are being sarcastic or not with this bit. 19th century cartridges will only appear in the 19th century at most in the late 18th century.(The Japanese call these shrimp butts by the way - not shrimp tails, shrimp butts; they're a localized version of a Wilson rifle - a type of rifle I have never heard of until finding this Japanese website)

If you decide that a Portuguese alchemist/pharmacist/witch will discover fulminates earlier in this timeline than in our own, and start using them in firearms (maybe taking that leap in making cartridges similar to the ones of the late nineteenth century which have the primer, powder, and bullet in one simple package), this could show how Portuguese guns might look. If you think it's plausible.

Besides, why not shrink a berço and make a berçete?

I did plan on making the Portuguese introduce bayonets in high quantities as soon as they are able but I did not know the Chinese had them that early. Yes, I can see the Portuguese adapting those at some point, I will look into that. The Portuguese Tercios are already slightly different from the Spanish ones as they have more musketeers/arquebusiers. My idea for a future Portuguese doctrine is to be very defensive with a heavy focus on firepower and accuracy with support from artillery and a Polish style cavalry but this will be shown eventually.P.S. I'm curious how you're going to introduce bayonets to the army (the Chinese were using them in the fifteen hundreds), and for how long will the Portuguese be using Tercios. Will they come up with something of their own?

It looks cool but the doublet needs to be dark blue instead of purple, no? Thank you for the comment.P.S.S.

I made this:

View attachment 868691

Supposed to be an eighteenth century Portuguese soldier from an alternate timeline, done in the style of Osprey military history. I did this just to show off my infantile nature.

I eagerly await the next chapter to your "Hestória do Reino e Império de Portugal - do reinado do D. Duarte II, até aos dias de hoje"

Glad you enjoy it, thank you for the comment.Amazing work as usual 🇵🇹🇵🇹

Youre amazing!Glad you enjoy it, thank you for the comment.

I wish it wasn't so realistic. I wish Portugal was more wanked.So in other words, this chapter wasn't realistic?

Gosh darn it.I can't tell if you are being sarcastic or not with this bit. 19th century cartridges will only appear in the 19th century at most in the late 18th century.

See what I mean when I said I didn't want this history to be too realistic?

Is there any possibility that the Portuguese might employ one Mr. Samuel Pauly?

I'm afraid Mr. Samuel Pauly will only arrive in the time frame it did OTL. I want things to be realistic and logical even if it ends in a Portuguese wank at the end of the day.I wish it wasn't so realistic. I wish Portugal was more wanked.

Gosh darn it.

See what I mean when I said I didn't want this history to be too realistic?

Is there any possibility that the Portuguese might employ one Mr. Samuel Pauly?

Lusitania

Donor

The biggest factor or pitfall I see in many TLs is that we have the same character in the same role or invent the same thing hundreds of years later. An example was a Portuguese TL that started in the 15th century; Portugal established a large colony in North America and then had the same king and prime minister as iOTL during the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake. That the earthquake happened is unavoidable; we have the same king and Prime Minister 300+ years in the future, which is not possible or sloppy writing.I'm afraid Mr. Samuel Pauly will only arrive in the time frame it did OTL. I want things to be realistic and logical even if it ends in a Portuguese wank at the end of the day.

Therefore, the invention can happen earlier if the right circumstances are in place for advancement in technology or science or happen later if the opposite is the case. For example, let's look at the discovery of the hot air balloon in the Portuguese empire in the 18th century. it ended in disaster, and hot air balloons were only invented and developed in France 50-80 years later. But what if the right circumstances had been in place and an individual did develop it and was adopted in the early 18th century? How that would have changed warfare.

As long as Portugal gets wankedI'm afraid Mr. Samuel Pauly will only arrive in the time frame it did OTL. I want things to be realistic and logical even if it ends in a Portuguese wank at the end of the day.

I don't really need to see Pauly's adventures in Portugal; I just want that gun, or something like it. The sooner, the better.The biggest factor or pitfall I see in many TLs is that we have the same character in the same role or invent the same thing hundreds of years later. An example was a Portuguese TL that started in the 15th century; Portugal established a large colony in North America and then had the same king and prime minister as iOTL during the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake. That the earthquake happened is unavoidable; we have the same king and Prime Minister 300+ years in the future, which is not possible or sloppy writing.

Therefore, the invention can happen earlier if the right circumstances are in place for advancement in technology or science or happen later if the opposite is the case. For example, let's look at the discovery of the hot air balloon in the Portuguese empire in the 18th century. it ended in disaster, and hot air balloons were only invented and developed in France 50-80 years later. But what if the right circumstances had been in place and an individual did develop it and was adopted in the early 18th century? How that would have changed warfare.

I need to correct myself regarding the Chinese use of bayonets. I said that they were using them in the fifteen hundreds, but the earliest document mentioning them dates to 1606.

Of course, it's a plug bayonet.

Of course, it's a plug bayonet.

For the sake of making things easier, because a TL starting in the 1550s is a big endeavour, I'm keeping a lot of royals as they were in OTL until I messed so much with the family trees that the royals are no longer recognizable. With common mortals, I'm thinking of keeping some individuals until like mid 18th Century such as Bartolomeu de Gusmão and after that, it will be Original Characters. I'm not a computer that can simulate something like Crusader Kings, it gets very messy and a lot of TLs who start changing royal marriages and children don't make it to fifty years after the POD.The biggest factor or pitfall I see in many TLs is that we have the same character in the same role or invent the same thing hundreds of years later. An example was a Portuguese TL that started in the 15th century; Portugal established a large colony in North America and then had the same king and prime minister as iOTL during the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake. That the earthquake happened is unavoidable; we have the same king and Prime Minister 300+ years in the future, which is not possible or sloppy writing.

Therefore, the invention can happen earlier if the right circumstances are in place for advancement in technology or science or happen later if the opposite is the case. For example, let's look at the discovery of the hot air balloon in the Portuguese empire in the 18th century. it ended in disaster, and hot air balloons were only invented and developed in France 50-80 years later. But what if the right circumstances had been in place and an individual did develop it and was adopted in the early 18th century? How that would have changed warfare.

As long as Portugal gets wanked

I don't really need to see Pauly's adventures in Portugal; I just want that gun, or something like it. The sooner, the better.

Portugal will slowly get wanked, the dice are set and the signs are there, it will take some time and while there will be Golden Ages (one of which soon), there will be other bad times. I will take a look at those bayonets at some point.I need to correct myself regarding the Chinese use of bayonets. I said that they were using them in the fifteen hundreds, but the earliest document mentioning them dates to 1606.

Of course, it's a plug bayonet.

Lusitania

Donor

The events will change, and in my opinion, we can have Pedro II instead of Joao IV. To make things simpler for us, we can have similar events, and they have similar attitudes and prejudices. In my example, Jose II and Marques Pombal dealt with the 1755 earthquake on a TL that started in 1450. Plus, Portugal had one of North America's largest reserves for shipbuilding, and its navy was the same size as iOTL.For the sake of making things easier, because a TL starting in the 1550s is a big endeavour, I'm keeping a lot of royals as they were in OTL until I messed so much with the family trees that the royals are no longer recognizable. With common mortals, I'm thinking of keeping some individuals until like mid 18th Century such as Bartolomeu de Gusmão and after that, it will be Original Characters. I'm not a computer that can simulate something like Crusader Kings, it gets very messy and a lot of TLs who start changing royal marriages and children don't make it to fifty years after the POD.

Portugal will slowly get wanked, the dice are set and the signs are there, it will take some time and while there will be Golden Ages (one of which soon), there will be other bad times. I will take a look at those bayonets at some point.

The Kingdom: Political Developments of the 1630s

The Kingdom: Political Developments of the 1630s

Reino: Dezenvolvimentos Políticos dos Anos de 1630

Reino: Dezenvolvimentos Políticos dos Anos de 1630

Relations with the Nobility

Filipe I as stated was a much more open-handed individual when it came to nobility, creating many new titles through his reign though without granting them privileges that could threaten his rule or the proper administration of the Kingdom as Monarchs such as Afonso V or Manuel I had done. Some of the most powerful families such as the Bragansas, Lencastres, the Menezes and a few more held control of the Ouvidorias which were effectively like the Comarcas (the administrative subdivisions below the Provinces but above the Municipalities) since pretty much the beginning of the Aviz Dynasty and they nominated the Ouvidores to represent them in judicial and administrative matters, reserving for them the right to choose the Alcaides of each Municipality they controlled.

Most of the titles he created had come from good military, diplomatic and administrative services but quite a few came from friendships with the King and in this sense, there was no major change from the previous reign or the practice of the day. However, many families were able to increase their power and wealth through well-made marriages akin to what was happening in Espanha or Fransa, a phenomenon that had been rather rare before Filipe’s reign but became prevalent in his reign, in part because some of the families died out likely because of consanguinity problems.

João II de Bragansa was the big catch of the marriage market in the Peninsula and beyond and while he received offers from the Estes of Modena, the Farnese of Parma and the Radevilas of Polónia-Lituânia, he was drawn to the offer made by Manuel Alonso de Gusmão, Duke of Medina Sidónia for his only surviving daughter Luíza de Gusmão because it brought more benefits for the House of Bragansa, including privileged commercial ties with Andaluzia and tying the two most powerful nobles families of the Peninsula.

Unbeknownst to João II, Manuel Alonso had been convinced of the benefits of the marriage by his cousin Gaspar de Gusmão, the Count-Duke of Olivares and effective ruler of Espanha, who saw this a counterweight to Filipe I of Portugal’s French-leaning stance. Despite the marriage creating a very powerful noble block, Olivares believed the benefits to the Spanish Crown outweighed the disadvantages though he would wish he could still offer his deceased daughter Maria de Gusmão who died in 1626 as it would have been less prejudicial to his position in Espanha than strengthening his very powerful kin.

The marriage was seen with some discomfort by Fransisco Coutinho who tried to have Filipe veto it but the King refused and even incentivized it. Defeated at first, Coutinho opted for a different approach and sought ways to turn Olivares’ scheme against him by getting closer to the main branch of the House of Gusmão, making them Portuguese-leaning and making Portugal prosper from the commerce with Andaluzia.

Thus, after negotiations the marriage between João II de Bragansa and Luíza de Gusmão was officialised on August 8, 1631, in the Cathedral of Évora by Archbishop Jozé de Melo, brother of Marquis Fransisco de Melo and thus a close kin to the Bragansas, with the presence of the King and Queen.

The bride’s elder brothers Gaspar Alonso de Gusmão, Count of Niébla and Melchior de Gusmão came with her and stayed in Vila Visoza for a while to shift the Bragansas into supporting Filipe IV of Espanha’s interests, and thus tacitly support Olivares’ interests as the Gusmãos de Medina Sidónia were jealous of his power. Nevertheless, João II de Bragansa was not a pro-Spanish noble like his father had been so their task was very difficult to accomplish though he did enjoy the company of Gusmãos.

It was for this reason that Olivares had Melchior nominated Spanish Ambassador in January 1632 after marrying the wealthy Luíza Jozefa de Estuniga [Luisa Josefa Manrique de Zúñiga y Guzmán], Marquess de Vila Manrique [Villamanrique] and a member of the powerful House of Estuniga of Basque origins. Using his new position, Melchior began meddling in Portuguese politics taking control over the Spanish faction in the country, after Izabel Clara Eujénia died in 1633, and became a good friend of Filipe I much to Queen Henrieta and the French faction’s dismay. His only son, Manuel Luíz de Estuniga e Gusmão was born in Vila Visoza a few months later on June 24.

The second most powerful noble family in the country, the Lencastres were still headed by the very influential widow, Juliana de Lencastre known as Juliana I de Aveiro. She had been a protegee of Queen Izabel de Médisis and was a good friend of Queen Izabel Clara Eujénia making her the most powerful woman in the country after the Royal Family and in old age was a very cunning lady with court experience who so far had witnessed five Kings. With her uncle and husband Álvaro I de Aveiro, she had sixteen children and with her connections, she managed to secure good weddings and positions for all of those who survived to adulthood.

Her eldest surviving son, Jorje Duarte de Lencastre died in 1632 without being able to inherit the title of Duke of Aveiro leaving three daughters from his wife Maria Béljica do Crato which created yet another succession crisis in the family this time between the eldest daughter of Jorje, Maria Juliana de Lencastre and her uncle Afonso Sebastião de Lencastre, Marquis of Porto Seguro.

Afonso Sebastião was a man with administrative experience Overseas having served as Vise-Rei da Índia and Governor of Brazil by this point. His mother had secured him a marriage with Ana de Sande e Padilha [Ana de Sande y Padilla] Marquess of Valdefontes [Valdefuentes] and Countess of Melhorada [Mejorada] which opened up a way for the House of Lencastre to spread into Espanha but this prevented him from marrying his niece and settle the succession crisis as his parents had done.

Instead, since his brother Pedro Jozé de Lencastre was at the time Bishop of São Salvador da Baía and had taken the chastity vows, Duchess Juliana chose her youngest son Luíz Barnabé who was still unmarried to marry the young Maria Juliana. Afonso Sebastião protested against this decision but Luíz Barnabé and Maria Juliana were married and requested that Filipe I sanctioned the inheritance which he did. Thus upon Juliana I’s death in 1636, Maria Juliana became Juliana II de Aveiro and Luíz Barnabé became Luíz I de Aveiro.

Afonso Sebastião, angered by this outcome, left for Espanha in 1635 and did not come to his mother’s funeral in protest. His branch of the family started working for Filipe IV de Espanha and its interests lay there from that point on. As for the new Dukes of Aveiro, their marriage did not have good results in the offspring department with five children produced, only two daughters Juliana Fransisca and Beatriz Henrieta survived their first day so it seemed like the family was once again up to a new succession crisis...

Another family that was on the rise were the Coutinhos. Despite lacking the honour of being a relative of the King, the family was one of the oldest titled ones having been prominent since at least Afonso V’s reign and being one of the very few that remained prosperous with João II. They lost their prominence during the 16th Century but regained it thanks to Fransisco Coutinho, Count of Olivais who had been João IV’s best friend and now the right-hand man of Filipe I who chose him to be his valido.

With the death of his nephew, also named Fransisco, in 1628, the Count of Olivais inherited the County of Redondo which combined with his owning the Captaincy of Santa Catarina in Brazil and investments in the Portuguese merchant companies made him a very wealthy and influential man, being the most powerful after the King himself, rivalling João II de Bragansa. In 1635, Filipe I upgraded the County of Olivais to a Marquisate and authorized the County of Redondo to be granted to Fransisco’s oldest son and heir João Fransisco Coutinho.

Fransisco Coutinho, Marquis of Olivais and Capitão Donatário of Santa Catarina

The House of Crato was another family on the rise in Portugal. Emília de Oranje-Nasau died in 1629 and not long after, her husband Manuel do Crato started having mistresses, including Indian women given that he held many administrative titles Overseas late in his life. For his services, he was elevated to Marquis and his eldest son and heir, Manuel António was made Count of Belver which became the heir’s title.

Both the father and the son enjoyed a good relationship with Filipe I and that made them get his support to have the marriage between Manuel António and Joana Forjaz Pereira, Countess of Feira, the most desirable bride in the country which made the Cratos very wealthy and powerful, a vast improvement from the poverty they endured before Manuel the Elder submitted to João IV. The couple would have three sons António Manuel born in 1623, Luíz Manuel born in 1625 and Fransisco António born in 1630.

But none of them could compare with the ascension of Filipe I’s best friend, Miguel de Drácula called “Miguel do Barco” [Michael of the Boat] by Filipe due to him being born on the boat that brought his mother, sister and grandmother to Lisboa. Due to being a Foreign Prince, João IV made him Baron of Valáquia, when the man returned from service in Polónia-Lituânia where he became an able cavalry commander, he was promoted to Viscount and before Filipe’s death he would become a Count and then a Marquis because of his many services. His marriage with Beatriz Luíza de Acolti, the only daughter of Luíz de Acolti, another of João IV’s friends also brought the County of Sangalhos to the family.

Many other families that were on the rise since João IV’s reign such as the Menezes de Vila Real, the Bragansas-Montemor, the Melos, the Ataídes, the Gamas and many others. But perhaps the most interesting episode was the Marquis of Valensa, Afonso II, whom Filipe I had rewarded for his father’s actions, and had to endure a very weird dispute with Filipe I because the King refused to allow anyone to have the surname de Portugal except the Infantes. Afonso was thus forced to adopt a new surname and chose de Valensa.

Royal Family

Henrieta once more got pregnant and went into labour on July 18, 1630. Despite the pain, her long labour resulted in the birth of a healthy baby boy which she insisted on being named Henrique after her father, Henrique IV of França. Filipe accepted her demand as he already had a son named after his father, and so Prince Henrique João Duarte de Portugal was baptized on July 28 in the Lisboa Cathedral with Luíz XIII da França being his godfather and his paternal aunts Leonor Izabel and Maria Catarina being his godmothers.

While the child was healthy, he soon showed some ailments namely that he was too quiet, did not display emotions and struggled to walk and talk despite being big for his age. Henrieta was deeply concerned with her son and nasty rumours started to spread about Henrique being possessed or retarded. Filipe despite it all, doted on his first legitimate son and made him Prince of the Algarves and Duke of Guimarães as soon as it was clear he would not die, this caused envy in his oldest bastard son João Duarte who at this point was 12 years old and was more sidelined, initiating one of the famous disputes in Portugal’s story.

The depressed Queen Dowager Izabel Clara Eujénia was named Henrique’s educator, giving her a purpose after her husband’s death which brought her some joy. With perseverance, Izabel managed to get her grandson to talk and walk through constant dialogue, usage of toys and reward-punishment mechanisms. On March 6, 1632, the Kingdom rejoiced with the birth of a Princess who was baptized Maria Henrieta Izabel and whose godfather was Filipe IV de Espanha and the godmothers were Izabel, Queen of Espanha and Cristina, Duchess of Savoia, Queen Henrieta’s sisters.

Maria Henrieta was a much livelier child, eager to explore her surroundings and she too was placed under the care of her paternal grandmother. Unfortunately, Izabel Clara Eujénia would die on December 1, 1633, at 67. Her death was grieved through the country and was Prince Henrique’s first experience with death which left him deeply uncomfortable despite being only 3 years old. Their new preceptor was Joana Margarida Corte-Real, Countess Dowager of Redondo who preferred to focus on Maria Henrieta rather than on Henrique because she lacked experience with raising boys, especially ones with Henrique’s ailments.

Henrieta would get pregnant again and give birth to another daughter on June 17, 1635. The Princess was named Leonor Catarina Eujénia and her godfather was Ladislau IV of Polónia-Lituânia and her godmothers were Ana Maria, Queen of França and Maria Ana, Empress of the Sacro-Império [Holy Roman Empire]. Two years later, on May 4, 1637, a second son was born, Duarte Filipe Luíz, who was made Duke of Beja from birth and whose godfather was Emperor Fernando III do Sacro-Império and whose godmothers were the Emperor’s sisters Maria Ana, Electress of Baviera and Sesília Renata, Queen of Polónia-Lituânia. Finally, to end the decade, on June 23, 1639, another daughter was born, Beatriz Izabel Maria, with João I da Toscânia as the godfather and his older sisters Izabel Maria, Duchess of Parma and Ana Catarina, Marquess of Brandemburgo-Ansbáque [Brandenburg-Ansbach] being the godmothers.

Portugal rejoiced with having so many Royal Children who were healthy and thriving. There were two boys, Henrique and Duarte and three girls, Maria, Leonor and Beatriz and it seemed the King and Queen were not done yet. Like Henrique, Duarte was a shy boy but capable of displaying emotions and eager to please while the sisters were talkative, spirited and a bit spoiled by their parents and preceptor.

By far, Henrique was the smartest, despite the difficulties the boy had to talk and walk earlier on, he had an easy time gripping various subjects including physical activities with the help of his unusually big size and strength but he was very shy and thus he struggled in social environments. Filipe I sought a Jezuíta in Salvador da Baía named António Vieira, famous as a great orator in Brazil to teach Prince Henrique how to improve his speech capabilities. These lessons began in 1637 when Henrique was still six and Vieira was according to his memoirs very surprised with the Prince who despite having difficulty focusing, showed intellect and a kind heart despite his aloof exterior.

Padre António Vieira

Unlike his lavish parents whom his sisters were already emulating despite their young age, Henrique was happy with little, disliking fancy clothes and often dressing like a soldier which was seen as a scandal and mocked by his half-brother João Duarte, then already made Count of Elvas, and whose jealous kept growing, a feeling none of his siblings (Pedro Filipe, Filipa Izabel and Ana Izabel, the bastard children of Filipe I and his former mistress Ana Barboza) shared, at least in such way.

To improve his social skills, Vieira had Henrique speak with other noble kids of his age in gatherings and parties about his likes, dislikes and simple mundane things to gain experience and easiness in conversations, being present to make sure the Prince did not give up. Henrique was rather joyful (according to his own words) with his progress until he overheard Pedro Fransisco Coutinho and sister Filipa Izabel Coutinho, grandchildren of the powerful Fransisco Coutinho mocking him in private.

The young Prince became depressed and refused to obey Vieira any longer much to the priest’s dismay. Young Fransisco António do Crato, the youngest grandson of Manuel do Crato, was the opposite of the Coutinhos and persistently tried to befriend the Prince as according to his chronicles (which are deemed quite unbiased), he was intrigued by the Prince who was always depressed and alone despite his position.

It was not easy for the young noble lad as Henrique could really close himself from others but Fransisco was very smart, bold, persistent and not a quitter, qualities that allowed him to succeed in life, so no matter how much Henrique pushed him away, he kept insisting and with Vieira’s support, the two of them managed to get the Prince to forget about the mean noble kids and focus in improving himself at getting better at talking. After months of persistent encouragement, Henrique resumed his attempts at holding conversations with other people though more sceptically than before. Vieira was thankful for the help he got from Fransisco António and he was the first to recognize the boy’s genius intellect, especially in strategy while playing chess with him and Prince Henrique.

The two of them were not the only ones concerned with Henrique’s depression, his parents were too and Filipe I decided to gather a bunch of noble kids to be educated with his son so that he could make friends. While the idea was noble, Filipe included kids from his own friends like Pedro Fransisco Coutinho, one of the sources of the Prince’s depression, though no one noticed it until Henrique became very defensive towards the boy who as a kid was not very nice.

Pedro Fransisco Coutinho, João da Silva, heir to the County of Portalegre, Lourenso de Corbizi, third son of the Count of Álvares and Pedro Miguel de Drácula, heir to County of Valáquia were a group of nobles that were all slightly older than Henrique and friendly to João de Elvas, the noble who served as the example to emulate in court given Henrique’s young age and Elvas’ charisma, who took advantage of their admiration towards him and their aggressive behaviour to make them bully Henrique and anyone who tried to befriend him.

It worked well because despite Henrique being the Prince, was isolated by the noble boys except for Fransisco António and Manuel Luíz de Estuniga e Gusmão, the son of Melchior de Gusmão who had befriended Henrique after he resumed his attempts at holding conversations. But even these two rather steadfast boys were pressured by the troublesome four to leave Henrique’s side and while according to Crato, Manuel was at one point almost giving up, Crato convinced him not to do so.

Unfortunately, the situation got out of hand when the four boys got into a particularly nasty argument with Henrique and his two friends and decided to fight them. According to Fransisco António’s writing: “Manuel was quickly beaten by Silva and Corbizi who cowardly attacked him together and was on the floor bleeding and crying while I avoided Coutinho and ran to get help as it was the most logical thing to do, though to this day I still regret not staying with Henrique. When I returned with some guards, Henrique had beaten the four of them by himself due to his absurd strength but he had taken a good beating too. Coutinho had passed out from just a punch and the others were crying in pain in pain with Corbizi passing out when we arrived. All the while Henrique had his hands closing his ears and claiming that he didn’t want to hurt them but they hurt him and Manuel.”

Since the young nobles attacked the Prince, they were exiled from court immediately after they recovered, being spared from harsher penalties such as death due to Filipe deeming them reckless kids who did not deserve death and no one really opposed his decision. For his side, Henrique tried to mend things with the parents, feeling worried about the four boys’ state though his efforts were met with mixed results while João de Elvas suffered no repercussions because nothing could be traced to him.

But his hatred towards Henrique was his undoing because he started denigrating his half-brother by claiming he had no control over himself and was a mindless brute. Henrieta Maria enraged by these statements demanded that Filipe send his bastard son away from court which he agreed to do though because of his love for all his children, Elvas would return a year later, after repenting himself, despite many criticizing the King’s decision to so, chief among them the Queen who tolerated all of Filipe’s bastards but not João de Elvas who she despised as much as the bastard despised her.

Elvas’s badmouthing prevented many young nobles from approaching Henrique but without the other boys bullying anyone who tried to get close to him, Henrique managed to befriend Luíz de Menezes, a brother of Fernando de Menezes, Count of Lourisal, who was two years younger but just like the Prince suffered from bouts of depression, the main reason why he had not approached earlier. Things seemed to have gotten better for the Prince of the Algarves but the hate of João de Elvas was not easily defeated.

Count João Duarte de Elvas

The Government Reform of 1630

Filipe I was not a Monarch too interested in ruling like his father had been so he preferred to delegate power to trusted advisors which were either his father’s own advisors or his friends. After two years when Filipe I reigned like his father, he decided to decree the 1630 Administration Reform which rivalled in importance the one his grandfather Duarte I had passed that created multiple councils to help him rule following the Spanish model.

The new Reform followed the French and English models of having a Government Cabinet. Filipe created or reformulated seven Ministries and Court positions:

- Secretário de Estado de Asistênsia ao Despacho [Secretary of State for Assistance of Dispatch] or the King’s right-hand man who conducted the country’s administration with the sanction of the King as if he were the King himself.

- Mordomo-Mor e Secretário de Estado da Caza do Rei [Lord Chamberlain and Secretary of State of the Royal Household] was responsible for administrating the Royal Household as it was before the Reform.

- Condestável de Portugal e Secretário de Estado da Guerra [Constable of Portugal and Secretary of State of War] responsible for the Army’s condition both in personnel and equipment as well as being the Supreme Commander of the Army after the King himself and thus needing to lead the Army in a war as it was before the Reform though it was no longer a decadent or hereditary position.

- Grão-Almirante de Portugal e Secretário de Estado da Marinha [Grand Admiral and Secretary of State of the Navy] was responsible for the Navy’s condition in both personnel and equipment as well as being the Supreme Commander of the Navy after the King himself and thus needing to lead the Navy in a war. This position replaced all the other offices such as Almirante de Portugal, Capitão-Mor do Mar, etc. that were hereditary.

- Chanceler-Mor e Secretário de Estado da Justisa [Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State of Justice] was responsible for the well conduct of justice in the country, the administration of all courthouses and publishment of all laws.

- Tezoureiro-Mor e Secretário de Estado da Fazenda [Lord High Treasurer and Secretary of State of the Exchequer] responsible for the economy of the country, the treasury (with the sanction of the Vedors da Fazenda [Treasurers]) and collection of revenues.

- Secretário de Estado das Relasões Exteriores [Secretary of State of Foreign Relations] responsible for the foreign diplomacy and coordination of the diplomats.

For the position of Assistance of Dispatch, he nominated his deceased father’s best friend Fransisco Coutinho, Marquis of Olivais who became his right-hand man and thus the second most powerful man in the Kingdom. Coutinho was a way for Filipe I to make sure he was pursuing his late father’s policies. His best friend Miguel Drácula was nominated for Mordomo-Mor while João II of Bragansa, already Constable received the office of Secretary of War as a formality tying the two positions together.

Afonso do Vimiozo, Marquis of Valensa was deprived of his title of Almirante de Portugal but was compensated by being nominated the first Grão-Almirante de Portugal because he did have experience in naval affairs. For Chanseler-Mor the Jezuíta André de Almada was the chosen one due to his experience while Filipe’s personal treasurer Jozé Luíz de Sampaio was given the position of Tezoureiro-Mor. Finally, Vasco António da Costa Corte-Real, Count of Angra was chosen for Secretary of Foreign Relations.

Most of the Ministers were members of the Second Estate (Nobility), with one being from the First Estate (Clergy) but whose roots were in the Second Estate and one being from the Third Estate (Commoners) and a New Christian. Sampaio did face some sneering from some of the Secretaries of State but overall, led by Coutinho, the group worked quite efficiently and safeguarded the interests of the country from the very beginning.

During the 1630s, only two changes were made in Foreign Relations, due to Corte-Real’s death on 12/02/1836, he was replaced by Luíz de Ataíde, Marquis of Santarém but his death in 11/03/1839 forced a new nomination to the position in the person of Antão de Almada, Count of Avranches.

The Government Cabinet system was a very important milestone for the country because now Monarchs that were less inclined to rule such as Filipe I or even more interested ones such as João IV were complemented by an efficient group of people that not only were focused on a specific administrative topic and thus better prepared to answer whatever problems might arise in that area but allowed the burden of rulership to be lessened. The new system was not without its problems. As stated, not everyone in the Government was especially friendly with each other and petty interests were always not far but at the end of the day, things did get more efficient.

Before anything, I'm very proud of surpassing the 100 000 views on the story. It's a big milestone and gives me the will to continue. I haven't finished revamping all of the older chapters but I will get there.

This is the first chapter of 2024. I tried to create political intrigue in a believable way but I'm not 100% sure of what I came up with as it's partly inspired by my fictional drama stories that sometimes exaggerate things. It also serves to set up things for the future and there are a few spoilers here and there. Anyway, I think that's all for now, thank you for sparing time reading and I hope everyone has a nice day and stays safe.

Last edited:

Very glad seeing this back!

@RedAquilla ! VERY happy it's back!

Thanks for the positive feedback. I'm currently working on the Military and Economy chapters for a while but I haven't gotten where I want it.Awsome to see this back , now waiting for an update of your other TL

As for the Vivam Lusos Valorosos, I do suck at abstracts/summaries (resumos) so I'm struggling a bit with keeping the international developments small but I have been writing a bit about the 1840s in the meantime.

Henrique really resonates with me for some reason I can't quite put my finger on...

Threadmarks

View all 62 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

The Great Religious War: The Netherlands and the Americas The Great Religious War: The Iberian Peninsula Polish-Swedish War Part 4 Europe: Between 1625 and 1628 The King's Death: An Appraisal King Filipe's First Year: The Pompous Year Europe: The Polish-Lithuanian Campaign The Kingdom: Political Developments of the 1630s

Share: