You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Pride Goes Before a Fall: A Revolutionary Greece Timeline

- Thread starter Earl Marshal

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan LeagueThe Party of Radicals will probably form around the same time as OTL as not much has changed in the Ionian Islands in this timeline.Earl,will the radical party in the ionian islands rise earlier that otl?

The Great Game will will likely be a concerning development for Greece as their two greatest allies are going to be at odds with one another, but so long as it doesn't break out into armed conflict between Britain and Russia, it shouldn't be too much of an issue for Greece.How will the Great game affect Greece? The one between Britain and russian because right about now it start to intensefy and start to head to a cold war level of aggression

Chapter 59: The Second Belgian Revolution

Chapter 59: The Second Belgian Revolution

Charles Rogier leading Belgian Revolutionaries through the Streets of Brussels

In many ways, the deposition of King Otto of Belgium on the 3rd of September 1847 did little to resolve the many issues facing the beleaguered Kingdom of Belgium. The widespread famine continued unabated across the countryside with thousands going hungry and hundreds more dying of starvation. The Belgian economy continued to falter as their Dutch and British competitors steadily bankrupted Belgian businesses and civil unrest continued to fester in Flanders as the Government continued to turn a blind eye to their plight and persecution. If anything, the deposition of King Otto created more problems for little Belgium than it solved as their relations with the Kingdom of Bavaria suffered extensively and the small German population in and around Luxembourg became increasingly embittered towards their government. Most worrying of all however, was the ensuing political instability which now gripped the Belgian Government.

Under the Belgian Constitution, the Sovereign retained considerable powers as Head of State, namely the ability to select and remove Ministers and his role as Commander in Chief of the Belgian military. Yet in this time of economic and political turmoil, it was paramount that the Belgian Government endow these powers upon someone. Many within the Belgian Government were inclined to replace Otto with a Prince from another royal house, providing Belgium with much needed diplomatic link to the established monarchies of Europe. Some desired King Louis-Philippe of France to take the Belgian crown for his own, while others wanted one of his sons as their king, a few wanted various princes and dukes from other royal houses, but none would succeed in gaining a majority vote by the Belgian Government.

These efforts to elect a new King were complicated by the emergence of various radical elements in Belgian society who were opposed to the institution of monarchy altogether. The followers of Victor Considerant, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Engles held great sway over the urban populace of Brussels who called for the abolition of the Monarchy and the establishment of a republic in its place.[1] Unsurprisingly, this measure of republicanism met with resistance by the conservative Catholic parties and members of the more moderate Liberal Party who feared the diplomatic isolation such a decision would entail. With the Belgian Parliament deadlocked, no definitive solution to their executive vacancy could be found. The only matter that could be agreed upon by all sides was the establishment of a Regency to hold the Head of State’s powers until a new sovereign was elected or until a republic was declared.

Unlike the earlier Belgian Regency by Baron Surlet de Chokier in 1831, this Regency was a council of nine men; Henri de Brouckère, Sylvain Van de Weyer, Alexandre Gendebien, Felix de Merode, Adolphe Deschamps, Albert Prisse, Jean Baptiste Nothomb, Pierre de Decker, and its chairman, the Revolutionary War hero Charles Rogier. These men were prominent figures of varying backgrounds and political inclinations in Belgian society, who were meant to provide an outward appearance of unity between Conservatives and Liberals, Walloons and Flemings; yet it would be just that, an appearance. The powers of the Regency Council were structured in such a way that any measure sent up from the Belgian Parliament could be passed into law on a simple majority vote and because the Council was comprised of 5 Liberals (Rogier, Brouckere, Van de Weyer, Gendebien, and Nothomb) to 4 Catholics (Merode, Deschamps, Prisse, and de Decker), the Liberals could generally approve whatever legislation they so desired and block whatever measures they did not.

The ethnic breakdown of the Council was also suspect as de Brouckère, Prisse, Nothomb, and Charles Rogier had been born and raised in France, while Van de Weyer, Felix de Merode, and Alexandre Gendebien openly supported French annexation of Belgium.[2] Adolphe Deschamps’ support for the Flemings was genuine due to his strong philanthropic nature, but he vacillated between benign neglect and modest advocacy towards them over the years. Only Pierre de Decker could be considered a stalwart ally of the Flemings and openly supported the continuance of King Otto’s controversial 1847 Language Ordinance, an act which earned him the ire of his compatriots in the Belgian Government. Sure enough, this disparity in the makeup of the Council would be seen in its first days as they would swiftly approve legislation undoing King Otto’s unilateral language dictate on a 7 to 2 vote, with only de Decker and Deschamps voting against. Although this decision was met with much outrage and protest by the Flemings, the Government paid it little heed initially and redirected its energies to other focuses.

Adolphe Deschamps (Left) and Pierre de Decker (Right)

With their political affairs sorted, the Belgian Government initiated various reforms intended to improve Belgium’s struggling economy. Large sums of Belgian Francs were spent to improve the antiquiated Belgian infrastructure system through the construction of new canals and railroads, aiding the movement of products from the countryside to the global market. The Belgian Government also hired unemployed artisans, engineers, merchants, and laborers to aid in the construction of these infastruction projects, providing employment to those in need. Sadly, these efforts did little to relieve the worsening famine in Belgium, forcing the Government to import vast quantities of food from overseas in order to feed its hungry people. While the influx of new products would help to relieve the hunger of the people somewhat and provide some people with temporary jobs, these efforts by the Government would unfortunately balloon the Belgian national debt at an alarming rate, necessitating a general increase in tax and tariff rates nationwide.

The sudden influx of cheap foreign foodstuffs would also harm the native Belgian agriculture industry as many small Walloon and Fleming farmers were forced to sell their own crops at a great loss in order to compete with the cheaper foreign products, leading many formerly self-sufficient farmers to fall into poverty. These developments in turn served to further the economic recession throughout the country which in turn resulted in a run on banks across the country as many sought to secure their capital in the event of a worsening economic crisis. Needless to say that is exactly what would happen as interest rates on British and French loans steadily increased in response to the political and economic instability of the country.

With the renewed persecution of their language and culture, combined with the worsening economic crisis, it would come as no surprise that Flemish demonstrations against the Belgian Government began to emerge across Flanders in mid-October 1847. From Antwerp and Mechelen to Bruges and Ghent, angered Flemings took to the streets demanding equal rights and equal protection under the law. They also demanded that the Government increase its investment into Flemish communities, as only 1 out of every 5 Belgian Francs collected through taxes and tariffs in Flanders made its way back to the region under the current investment system. Most protests were peaceful in nature, although some tended to be rowdier than others leading to a number of arrests and a few injuries, but nothing outside the norm for 19th Century protests. This situation would continue for several weeks before tragically changing for the worse following an incident in the coastal city of Oostende in early November 1847.

On the 9th of November, a large crowd of impoverished and malnourished Flemish men and women from the countryside descended upon the city of Oostende. Numbering somewhere between 300 to 400 people, the famished Flemings hoped to find food for themselves and their families in the bustling port town as a shipment of grain, fruits, and fish had arrived at the docks in recent days. With the Dutch still baring Belgian ships from the Scheldt, Oostende had been forced to develop from a tiny fishing hovel in the 1820’s to a major commercial port where foreign goods arrived by the shipload every day. Sadly for these men and women, their efforts to find sustenance would be hindered by the presence of a Garde Civique platoon which had been dispatched to the city to keep the peace. Mistaking the large crowd for a separate protest taking place across town, the soldiers refused to let the crowd pass to the markets beyond them, much to the Flemings’ dismay.

Undeterred, several men and women began pushing and shoving the soldiers in an attempt to get past them as hunger and desperation overcame rationality and self-preservation. Unfortunately, these efforts would be met with the butt of the guards’ rifles and the point of their bayonets. As tensions continued to mount, some angered Flemings resorted to throwing whatever they could find, with a few tossing bottles and cans, while others threw bricks and paving stones at the soldiers. One Guardsman was struck in the head with a stone, knocking him unconscious, while three more were brought to their knees by the flying debris. Having seen enough, one nervous soldier fired into the air to scare away the crowd, however, this warning shot would unfortunately elicit a volley of gunfire from his comrades into the ranks of the Flemings before them. The lead bullets ripped through the haggard crowd with ruthless efficiency, killing a dozen and maiming several more in a macabre spectacle of blood and guts. Fearing for their lives, the remaining Flemings fled in any which way they could, providing a quick and panicked ending to the once peaceful movement. While no one knew it at the time, the first shots of the Second Belgian Revolution had now been fired.

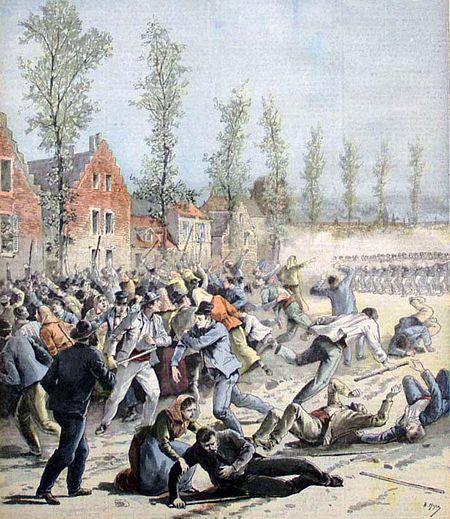

The Oostende Massacre

After two days of investigations and deliberations, the Belgian Government announced that it would not bring charges against any of the Guardsmen involved in the massacre, leading Pierre de Decker to resign in protest, with Adolphe Deschamps’ resignation the following week on the 17th. The Oostende Massacre would prove disastrous for the Belgian Government as Flemish protestors became increasingly violent and forceful in their demonstrations, leading the Regency to react in kind. Brussels would temporarily outlaw all public demonstrations across Flanders on the 25th of November in an attempt to curtail unrest. Yet, when this measure proved insufficient in ending the protests, they mobilized the Garde Civique across Flanders on the 1st of December, effectively declaring martial law in the north of the Country. While these efforts had been intended to undercut the growing turmoil in Belgium, they unfortunately had the reverse effect as violent clashes between protestors and guardsmen become more frequent, not less.

One such incident would see an entire company of Guardsmen brutalized by a frenzied Fleming mob in Louvain leading to vicious acts of reprisals by enraged soldiers in other Flemish cities. One last attempt for peace between the Flemings and the Walloons was held on the 7th of December, as the Flemish representatives Pierre de Decker and Jan Frans Willems made a humble request upon their Walloon countrymen for equal rights and equal protection for the Flemings under the law. Despite attending these talks in good faith, de Decker and Willems were betrayed by the Belgian Government and imprisoned for allegedly inciting sedition against the lawful Belgian Government. For the angry Flemings, this was the last straw, and within a matter of days all of Flanders was up in arms. The uprising of the Flemings would lead many states in Europe to look on with concern and trepidation, while others looked on with great interest and anticipation. None more so than the Kingdom of the Netherlands and its King William II.

Having succeeded his father, King William I as the ruler of the Netherlands in 1842, William II presented a much more nuanced stance towards the Southern Provinces than his rigid father. While he tepidly maintained the Netherlands’ old claim to the region thanks to the lack of pressure by the British and the other Powers, he also possessed a personal attachment to the region having spent much of his youth in Antwerp and Brussels.[3] William II also presented a more moderate sovereign than his father, as he generally stayed clear of politics and made sensible reforms when necessary enabling the Netherlands to avoid much of the economic and political turmoil which was plaguing the rest of Europe. King William II also recognized that many Flemings within Belgium still remained loyal to the House of Orange and the Kingdom of the Netherlands to some degree, a feeling that was only heightened after recent events in Belgium, and he would choose to act upon that sentiment with all the means available to him.

King William II of the Netherlands

To that end, King William II authorized smugglers to transport arms and munitions across the border into Belgium where they would be provided to Flemish partisans at a great discount. The Flemings eager for support, readily accepted the Dutch offer of weapons and began fighting against their Walloon oppressors with increasing efficiency. Roving bands of Fleming militiamen would fall upon hapless Civic Guardsmen with near impunity. One such battle in Bruges would see an entire battalion of Guardsmen cut down to a man by the ravenous Flemish mob, while another engagement in Mechelen would see the entire Garde Civique driven from the city after a fierce firefight with the rebels. With Winter fast approaching and the professional Belgian Army hesitant to march North so late in the campaign season, the beleaguered Garde Civique was gradually forced to abandon much of Flanders to the rebels.

Utilizing the lull in the fighting, the Flemings would declare their independence from Belgium on the 24th of December, establishing the Flemish State or Republic of Flanders as it was called by its contemporaries. They would establish a Provisional Government in the city of Antwerp and elect the Ghent lawyer Hippolyte Metdepenningen as its first President. Moreover, the Flemish State began seeking international recognition and support for their cause. Aside from the Netherlands, they received little formal recognition or aid from any other country in Europe, although some proved more receptive than others. France was strongly against them however, viewing any alteration of Belgium’s territorial integrity to be contrary to their interests in the region. The Belgian Government in Brussels, which by this time was a Walloon government for all intents and purposes, strongly opposed the loss of their northern provinces on a purely economic basis as well and vowed to reclaim them as soon as the weather allowed them.

When the Winter snows finally started to clear in late February 1848, the small Belgian Army some 12,000 strong, began its advance North from Brussels to Antwerp seeking to crush the Flemish rebellion in one fell swoop. The Flemings in response quickly mustered a force numbering over 14,000, which was supported by a small cadre of 1,200 Dutch volunteers, before sallying forth to combat their foe, meeting them near the town of Mechelen. Despite boasting more fighters than their Walloon adversaries, the Flemings were at a major disadvantage, lacking both the discipline and capable leadership of their adversaries as no one man held the reins of leadership in the army. Their cavalry and artillery were also severally lacking, and many men were armed only with clubs and polearms, rather than muskets and rifles. Matters were made worse for the Flemings as most of their men were untrained militiamen or irregulars as most Fleming soldiers in the Belgian army had been detained by the Belgian Government in the weeks leading up to the fighting between them.

The Walloons in contrast had benefited from years of French training, they were fully equipped with French armaments, and a number of French volunteer officers commanded several regiments within the small Belgian army. They boasted a larger cavalry contingent than their Fleming adversaries and they maintained a sufficiently large artillery train of 24 cannons compared to the 7 small cannons the Flemings possessed. They were also directed by the Walloon General Pierre Emmanuel Felix Chazal whose years of experience in both the French and Belgian armies made him a capable commander of men. Suffice to say, the professional Belgian army was more than a match for the rowdy and wild Flemish force sent to oppose them.

Despite these disadvantages, the Flemings felt confident in their chances for victory against the Walloons, trusting that their greater numbers and high morale would carry the day. Rather than wait for the Walloons to attack them, the Flemings threw caution to the wind and boldly charged the advancing soldiers as they crossed the River Nete north of Mechelen. Overcoming the initial shock, the Belgians bravely held their ground in the freezing waters of the Nete against the wave of Fleming rebels and unloaded volley after volley into their charging adversary, killing or maiming scores of enemy combatants. Despite this the Flemings would reach the Belgian lines initiating a fierce hand to hand melee between the two sides. After several dreadful minutes, the stalemate would be broken as the pitiful Fleming horsemen scattered before the superior Belgian cavalrymen, who then turn their sights onto the exposed Fleming infantrymen. With their flanks and rear exposed, several Flemings panicked and fled the field of battle sparking a cascade effect of fear and trepidation across the entire army. They were only saved from complete destruction at the hands of the Belgians thanks to the efforts of the Dutch volunteer regiment which bravely served in a rearguard duty to protect the Fleming’s retreat from the field of battle. Despite enduring ghastly casualties, the Dutch soldiers stubbornly held their ground for several hours, before retreating in good order themselves as night began to fall.

The Belgian (Walloon) Army in 1848

Despite the heroics of the Dutchmen, the Battle of Louvain was a complete disaster for the Flemish rebels who would lose nearly 3,000 men, most of whom were killed in the disorderly retreat to Antwerp, while another 2,000 would desert the cause all together in the days that followed, while the Walloons in comparison only lost 700 men. The next few days would serve as preliminary actions for the ensuing siege of Antwerp as both sides settled in for a protracted siege of the city after an assualt by the Belgian forces failed to take the city on the 5th of March. Skirmishes would take place between both sides on a frequent basis, with battles occurring near Beveren, Burcht, Doel, Edegem, Kapellen Mortsel, and Schoten. To impede their opponents, the Fleming Soldiers resorted to destroying the dams and dikes around the city, turning the rolling plains into a marshy bog. Nevertheless, the Belgians met with some success taking the strategic hamlets of Edegem and Mortsel on the 7th, Burcht and Schoten would fall to the Government’s troops on the 11th, and Beveren would capitulate two days later.

By late March, only a precarious route along the banks of the Scheldt remained open to the Flemings who desperately dispatched messengers down the river seeking aid from Amsterdam. King William II and the Dutch Government would prove very eager to assist their Fleming kinsmen and readily agreed to their requests for military aid on the condition of the immediate reunification of Flanders and the Netherlands. As a Walloon victory would likely mean their imprisonment or deaths, the Flemish Provisional Government had little recourse but to accept the Dutch Government's demands and so on the 9th of April, 40,000 Dutch soldiers poured across the border into Flanders.

Caught off guard by the sudden intervention of the Dutch, the Walloon forces were quickly overwhelmed by the combined Fleming-Dutch force at Antwerp. Despite the skill and tenacity of the Belgian General Chazal, his men were outmatched by the Dutch force under the Prince of Orange and was quickly forced into retreat. In a matter of days, the situation in Belgium had completely reversed as the Flemings and Dutch drove the Walloons southward towards Brussels. Unable to mount a proper resistance against the approaching Orangemen, the Belgian Government was forced to abandon Brussels to the approaching Dutch army on the 13th of April. While the fall of Brussels would cause the Fleming-Dutch Army to pause for some time, many within the Dutch Government and military desired the complete reconquest of the Southern Provinces and pushed for the Army to advance south into Wallonia, which it would do on the 16th of April. Fearing a complete collapse in their positioning, the Belgian Government invoked the 1831 Treaty of London and called upon the Powers for assistance against the Netherlands.

Despite their own internal unrest and economic instability, the Kingdom of France immediately heeded the call to arms almost immediately and began moving forces towards their border with Belgium. After some delay, Prussia also began moving troops towards its border with the Low Countries, while Austria and Russia remained quiet. Given their own internal unrest and distance from the theater, their silence was generally ignored by all parties. Most surprising of all however, was Britain’s overt refusal to meaningfully assist the Belgian Government in its fight against the Netherlands.

Despite being a signer of the 1831 Treaty of London, Britain was reluctant to aid a state, which for all intents and purposes in their eyes was a French satellite. French influence in Belgium had been a cause for concern under the deposed King Otto, and many had hoped that his removal from power would bring a friendlier government to power in Brussels. Yet London would be greatly disappointed when the new Walloon dominated Government continued its turn towards France, with many prominent ministers and representatives openly clamoring for the unification of Belgium with France. Britain had also begun rapprochement with the Netherlands in recent years and it had signed various trade deals that they were hard pressed to abandon given the strong economic ties between them. While the events in the Low Countries were certainly troublesome, other matters also drew London's attention.

In Central Asia the Persian Army of Mohammad Shah Qajar had boldly crossed the border into the Emirate of Afghanistan and captured the city of Herat in less than a month, shocking British agents in the region who doubted the Persians could manage such a feat. This resurgence of Persian power in Central Asia posed a significant threat to British interests in India necessitating that more military assets to be redirected to the Subcontinent. This development in Asia also reeked of French meddling, making any semblance of cooperation between Britain and France in the Low Countries an unseemly decision for the British government. Other theaters also required London’s attention, namely the Ionian Island which were clamoring for Enosis with Greece and Ireland which was clamoring for food for its starving masses. Like the rest of Europe, Britain was also struggling from economic and political upheaval of its own which limited the state’s ability to make war and the ongoing potato famine hurt Ireland immensely leading to constant unrest on the island. The growth of Socialism and Fourierism in Belgium also soured Westminster's opinion of the Belgian Government as these movements shared much in common with the damnable Charterist movement in Britain. As these groups held great influence over the Belgian Government's proceedings and measures an unfortunate correlation between the two grew as a result in London.

Nevertheless, Britain was bound by treaty to aid the Belgians should their territorial integrity be violated by any power, be it a friend or a foe. To that end, they would dispatch several ships of the Western Squadron of the Royal Navy to patrol the waters off Belgium’s coast, interdicting any Dutch vessels found in their waters. While this was deemed unsatisfactory to the embattled Belgian Government, Britain remained unconcerned with the Walloon complaints as they had technically fulfilled the terms of the treaty despite doing little to actually aid the Belgians on the ground.

With Britain ostensibly in the war and a French army some 84,000 strong under the command of the veteran commander, Marshal Thomas Robert Bugeaud, duc d’Isly marching to the Walloons aid, the Flemish and Dutch began withdrawing to their defensive positions North of Brussels where they would prepare for the coming attack. Between the 18th of April and the 5th of May a handful of skirmishes and sorties would take place between rearguard units of the Dutch army and advanced units of the French Army, but before the might of the French army the Dutch force of some 45,000 men stood little chance. Over the course of two weeks, the Dutch and Flemings were steadily forced northward by the superior French army. Making matters worse were a series of reports on the movement of a 63,000 strong Prussian army under the command of the Prince of Prussia, that was marching on their position with great haste. However, unbeknownst to both sides, Prince Wilhelm of Prussia had no intention of aiding the French and their Walloon allies. On the 6th of May, 1848, Prussian General Moritz von Hirschfeld and the 15th Division of the Prussian 1st Army opened fire on elements of the French army North of Liege revealing their entrance into the Second Belgian Revolution alongside the Dutch and Flemings.

Next Time: The Fire Spreads

[1] Around the time of the 1848 Revolutions in OTL, Karl Marx was indeed active in and around Brussels.

[2] Technically, Brouckère and Van de Weyer were born in French occupied Flanders during the Napoleonic Wars, but as noblemen from French speaking households they held strong affinities to France and the Walloons that would shape their politics.

[3] Due to increased tension between Britain and France, and by virtue Britain and Belgium, the Dutch have managed to avoid completely abandoning their claims to Belgium which has helped the Orangist movement in Flanders ITTL.

Charles Rogier leading Belgian Revolutionaries through the Streets of Brussels

In many ways, the deposition of King Otto of Belgium on the 3rd of September 1847 did little to resolve the many issues facing the beleaguered Kingdom of Belgium. The widespread famine continued unabated across the countryside with thousands going hungry and hundreds more dying of starvation. The Belgian economy continued to falter as their Dutch and British competitors steadily bankrupted Belgian businesses and civil unrest continued to fester in Flanders as the Government continued to turn a blind eye to their plight and persecution. If anything, the deposition of King Otto created more problems for little Belgium than it solved as their relations with the Kingdom of Bavaria suffered extensively and the small German population in and around Luxembourg became increasingly embittered towards their government. Most worrying of all however, was the ensuing political instability which now gripped the Belgian Government.

Under the Belgian Constitution, the Sovereign retained considerable powers as Head of State, namely the ability to select and remove Ministers and his role as Commander in Chief of the Belgian military. Yet in this time of economic and political turmoil, it was paramount that the Belgian Government endow these powers upon someone. Many within the Belgian Government were inclined to replace Otto with a Prince from another royal house, providing Belgium with much needed diplomatic link to the established monarchies of Europe. Some desired King Louis-Philippe of France to take the Belgian crown for his own, while others wanted one of his sons as their king, a few wanted various princes and dukes from other royal houses, but none would succeed in gaining a majority vote by the Belgian Government.

These efforts to elect a new King were complicated by the emergence of various radical elements in Belgian society who were opposed to the institution of monarchy altogether. The followers of Victor Considerant, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Engles held great sway over the urban populace of Brussels who called for the abolition of the Monarchy and the establishment of a republic in its place.[1] Unsurprisingly, this measure of republicanism met with resistance by the conservative Catholic parties and members of the more moderate Liberal Party who feared the diplomatic isolation such a decision would entail. With the Belgian Parliament deadlocked, no definitive solution to their executive vacancy could be found. The only matter that could be agreed upon by all sides was the establishment of a Regency to hold the Head of State’s powers until a new sovereign was elected or until a republic was declared.

Unlike the earlier Belgian Regency by Baron Surlet de Chokier in 1831, this Regency was a council of nine men; Henri de Brouckère, Sylvain Van de Weyer, Alexandre Gendebien, Felix de Merode, Adolphe Deschamps, Albert Prisse, Jean Baptiste Nothomb, Pierre de Decker, and its chairman, the Revolutionary War hero Charles Rogier. These men were prominent figures of varying backgrounds and political inclinations in Belgian society, who were meant to provide an outward appearance of unity between Conservatives and Liberals, Walloons and Flemings; yet it would be just that, an appearance. The powers of the Regency Council were structured in such a way that any measure sent up from the Belgian Parliament could be passed into law on a simple majority vote and because the Council was comprised of 5 Liberals (Rogier, Brouckere, Van de Weyer, Gendebien, and Nothomb) to 4 Catholics (Merode, Deschamps, Prisse, and de Decker), the Liberals could generally approve whatever legislation they so desired and block whatever measures they did not.

The ethnic breakdown of the Council was also suspect as de Brouckère, Prisse, Nothomb, and Charles Rogier had been born and raised in France, while Van de Weyer, Felix de Merode, and Alexandre Gendebien openly supported French annexation of Belgium.[2] Adolphe Deschamps’ support for the Flemings was genuine due to his strong philanthropic nature, but he vacillated between benign neglect and modest advocacy towards them over the years. Only Pierre de Decker could be considered a stalwart ally of the Flemings and openly supported the continuance of King Otto’s controversial 1847 Language Ordinance, an act which earned him the ire of his compatriots in the Belgian Government. Sure enough, this disparity in the makeup of the Council would be seen in its first days as they would swiftly approve legislation undoing King Otto’s unilateral language dictate on a 7 to 2 vote, with only de Decker and Deschamps voting against. Although this decision was met with much outrage and protest by the Flemings, the Government paid it little heed initially and redirected its energies to other focuses.

Adolphe Deschamps (Left) and Pierre de Decker (Right)

With their political affairs sorted, the Belgian Government initiated various reforms intended to improve Belgium’s struggling economy. Large sums of Belgian Francs were spent to improve the antiquiated Belgian infrastructure system through the construction of new canals and railroads, aiding the movement of products from the countryside to the global market. The Belgian Government also hired unemployed artisans, engineers, merchants, and laborers to aid in the construction of these infastruction projects, providing employment to those in need. Sadly, these efforts did little to relieve the worsening famine in Belgium, forcing the Government to import vast quantities of food from overseas in order to feed its hungry people. While the influx of new products would help to relieve the hunger of the people somewhat and provide some people with temporary jobs, these efforts by the Government would unfortunately balloon the Belgian national debt at an alarming rate, necessitating a general increase in tax and tariff rates nationwide.

The sudden influx of cheap foreign foodstuffs would also harm the native Belgian agriculture industry as many small Walloon and Fleming farmers were forced to sell their own crops at a great loss in order to compete with the cheaper foreign products, leading many formerly self-sufficient farmers to fall into poverty. These developments in turn served to further the economic recession throughout the country which in turn resulted in a run on banks across the country as many sought to secure their capital in the event of a worsening economic crisis. Needless to say that is exactly what would happen as interest rates on British and French loans steadily increased in response to the political and economic instability of the country.

With the renewed persecution of their language and culture, combined with the worsening economic crisis, it would come as no surprise that Flemish demonstrations against the Belgian Government began to emerge across Flanders in mid-October 1847. From Antwerp and Mechelen to Bruges and Ghent, angered Flemings took to the streets demanding equal rights and equal protection under the law. They also demanded that the Government increase its investment into Flemish communities, as only 1 out of every 5 Belgian Francs collected through taxes and tariffs in Flanders made its way back to the region under the current investment system. Most protests were peaceful in nature, although some tended to be rowdier than others leading to a number of arrests and a few injuries, but nothing outside the norm for 19th Century protests. This situation would continue for several weeks before tragically changing for the worse following an incident in the coastal city of Oostende in early November 1847.

On the 9th of November, a large crowd of impoverished and malnourished Flemish men and women from the countryside descended upon the city of Oostende. Numbering somewhere between 300 to 400 people, the famished Flemings hoped to find food for themselves and their families in the bustling port town as a shipment of grain, fruits, and fish had arrived at the docks in recent days. With the Dutch still baring Belgian ships from the Scheldt, Oostende had been forced to develop from a tiny fishing hovel in the 1820’s to a major commercial port where foreign goods arrived by the shipload every day. Sadly for these men and women, their efforts to find sustenance would be hindered by the presence of a Garde Civique platoon which had been dispatched to the city to keep the peace. Mistaking the large crowd for a separate protest taking place across town, the soldiers refused to let the crowd pass to the markets beyond them, much to the Flemings’ dismay.

Undeterred, several men and women began pushing and shoving the soldiers in an attempt to get past them as hunger and desperation overcame rationality and self-preservation. Unfortunately, these efforts would be met with the butt of the guards’ rifles and the point of their bayonets. As tensions continued to mount, some angered Flemings resorted to throwing whatever they could find, with a few tossing bottles and cans, while others threw bricks and paving stones at the soldiers. One Guardsman was struck in the head with a stone, knocking him unconscious, while three more were brought to their knees by the flying debris. Having seen enough, one nervous soldier fired into the air to scare away the crowd, however, this warning shot would unfortunately elicit a volley of gunfire from his comrades into the ranks of the Flemings before them. The lead bullets ripped through the haggard crowd with ruthless efficiency, killing a dozen and maiming several more in a macabre spectacle of blood and guts. Fearing for their lives, the remaining Flemings fled in any which way they could, providing a quick and panicked ending to the once peaceful movement. While no one knew it at the time, the first shots of the Second Belgian Revolution had now been fired.

The Oostende Massacre

After two days of investigations and deliberations, the Belgian Government announced that it would not bring charges against any of the Guardsmen involved in the massacre, leading Pierre de Decker to resign in protest, with Adolphe Deschamps’ resignation the following week on the 17th. The Oostende Massacre would prove disastrous for the Belgian Government as Flemish protestors became increasingly violent and forceful in their demonstrations, leading the Regency to react in kind. Brussels would temporarily outlaw all public demonstrations across Flanders on the 25th of November in an attempt to curtail unrest. Yet, when this measure proved insufficient in ending the protests, they mobilized the Garde Civique across Flanders on the 1st of December, effectively declaring martial law in the north of the Country. While these efforts had been intended to undercut the growing turmoil in Belgium, they unfortunately had the reverse effect as violent clashes between protestors and guardsmen become more frequent, not less.

One such incident would see an entire company of Guardsmen brutalized by a frenzied Fleming mob in Louvain leading to vicious acts of reprisals by enraged soldiers in other Flemish cities. One last attempt for peace between the Flemings and the Walloons was held on the 7th of December, as the Flemish representatives Pierre de Decker and Jan Frans Willems made a humble request upon their Walloon countrymen for equal rights and equal protection for the Flemings under the law. Despite attending these talks in good faith, de Decker and Willems were betrayed by the Belgian Government and imprisoned for allegedly inciting sedition against the lawful Belgian Government. For the angry Flemings, this was the last straw, and within a matter of days all of Flanders was up in arms. The uprising of the Flemings would lead many states in Europe to look on with concern and trepidation, while others looked on with great interest and anticipation. None more so than the Kingdom of the Netherlands and its King William II.

Having succeeded his father, King William I as the ruler of the Netherlands in 1842, William II presented a much more nuanced stance towards the Southern Provinces than his rigid father. While he tepidly maintained the Netherlands’ old claim to the region thanks to the lack of pressure by the British and the other Powers, he also possessed a personal attachment to the region having spent much of his youth in Antwerp and Brussels.[3] William II also presented a more moderate sovereign than his father, as he generally stayed clear of politics and made sensible reforms when necessary enabling the Netherlands to avoid much of the economic and political turmoil which was plaguing the rest of Europe. King William II also recognized that many Flemings within Belgium still remained loyal to the House of Orange and the Kingdom of the Netherlands to some degree, a feeling that was only heightened after recent events in Belgium, and he would choose to act upon that sentiment with all the means available to him.

King William II of the Netherlands

To that end, King William II authorized smugglers to transport arms and munitions across the border into Belgium where they would be provided to Flemish partisans at a great discount. The Flemings eager for support, readily accepted the Dutch offer of weapons and began fighting against their Walloon oppressors with increasing efficiency. Roving bands of Fleming militiamen would fall upon hapless Civic Guardsmen with near impunity. One such battle in Bruges would see an entire battalion of Guardsmen cut down to a man by the ravenous Flemish mob, while another engagement in Mechelen would see the entire Garde Civique driven from the city after a fierce firefight with the rebels. With Winter fast approaching and the professional Belgian Army hesitant to march North so late in the campaign season, the beleaguered Garde Civique was gradually forced to abandon much of Flanders to the rebels.

Utilizing the lull in the fighting, the Flemings would declare their independence from Belgium on the 24th of December, establishing the Flemish State or Republic of Flanders as it was called by its contemporaries. They would establish a Provisional Government in the city of Antwerp and elect the Ghent lawyer Hippolyte Metdepenningen as its first President. Moreover, the Flemish State began seeking international recognition and support for their cause. Aside from the Netherlands, they received little formal recognition or aid from any other country in Europe, although some proved more receptive than others. France was strongly against them however, viewing any alteration of Belgium’s territorial integrity to be contrary to their interests in the region. The Belgian Government in Brussels, which by this time was a Walloon government for all intents and purposes, strongly opposed the loss of their northern provinces on a purely economic basis as well and vowed to reclaim them as soon as the weather allowed them.

When the Winter snows finally started to clear in late February 1848, the small Belgian Army some 12,000 strong, began its advance North from Brussels to Antwerp seeking to crush the Flemish rebellion in one fell swoop. The Flemings in response quickly mustered a force numbering over 14,000, which was supported by a small cadre of 1,200 Dutch volunteers, before sallying forth to combat their foe, meeting them near the town of Mechelen. Despite boasting more fighters than their Walloon adversaries, the Flemings were at a major disadvantage, lacking both the discipline and capable leadership of their adversaries as no one man held the reins of leadership in the army. Their cavalry and artillery were also severally lacking, and many men were armed only with clubs and polearms, rather than muskets and rifles. Matters were made worse for the Flemings as most of their men were untrained militiamen or irregulars as most Fleming soldiers in the Belgian army had been detained by the Belgian Government in the weeks leading up to the fighting between them.

The Walloons in contrast had benefited from years of French training, they were fully equipped with French armaments, and a number of French volunteer officers commanded several regiments within the small Belgian army. They boasted a larger cavalry contingent than their Fleming adversaries and they maintained a sufficiently large artillery train of 24 cannons compared to the 7 small cannons the Flemings possessed. They were also directed by the Walloon General Pierre Emmanuel Felix Chazal whose years of experience in both the French and Belgian armies made him a capable commander of men. Suffice to say, the professional Belgian army was more than a match for the rowdy and wild Flemish force sent to oppose them.

Despite these disadvantages, the Flemings felt confident in their chances for victory against the Walloons, trusting that their greater numbers and high morale would carry the day. Rather than wait for the Walloons to attack them, the Flemings threw caution to the wind and boldly charged the advancing soldiers as they crossed the River Nete north of Mechelen. Overcoming the initial shock, the Belgians bravely held their ground in the freezing waters of the Nete against the wave of Fleming rebels and unloaded volley after volley into their charging adversary, killing or maiming scores of enemy combatants. Despite this the Flemings would reach the Belgian lines initiating a fierce hand to hand melee between the two sides. After several dreadful minutes, the stalemate would be broken as the pitiful Fleming horsemen scattered before the superior Belgian cavalrymen, who then turn their sights onto the exposed Fleming infantrymen. With their flanks and rear exposed, several Flemings panicked and fled the field of battle sparking a cascade effect of fear and trepidation across the entire army. They were only saved from complete destruction at the hands of the Belgians thanks to the efforts of the Dutch volunteer regiment which bravely served in a rearguard duty to protect the Fleming’s retreat from the field of battle. Despite enduring ghastly casualties, the Dutch soldiers stubbornly held their ground for several hours, before retreating in good order themselves as night began to fall.

The Belgian (Walloon) Army in 1848

Despite the heroics of the Dutchmen, the Battle of Louvain was a complete disaster for the Flemish rebels who would lose nearly 3,000 men, most of whom were killed in the disorderly retreat to Antwerp, while another 2,000 would desert the cause all together in the days that followed, while the Walloons in comparison only lost 700 men. The next few days would serve as preliminary actions for the ensuing siege of Antwerp as both sides settled in for a protracted siege of the city after an assualt by the Belgian forces failed to take the city on the 5th of March. Skirmishes would take place between both sides on a frequent basis, with battles occurring near Beveren, Burcht, Doel, Edegem, Kapellen Mortsel, and Schoten. To impede their opponents, the Fleming Soldiers resorted to destroying the dams and dikes around the city, turning the rolling plains into a marshy bog. Nevertheless, the Belgians met with some success taking the strategic hamlets of Edegem and Mortsel on the 7th, Burcht and Schoten would fall to the Government’s troops on the 11th, and Beveren would capitulate two days later.

By late March, only a precarious route along the banks of the Scheldt remained open to the Flemings who desperately dispatched messengers down the river seeking aid from Amsterdam. King William II and the Dutch Government would prove very eager to assist their Fleming kinsmen and readily agreed to their requests for military aid on the condition of the immediate reunification of Flanders and the Netherlands. As a Walloon victory would likely mean their imprisonment or deaths, the Flemish Provisional Government had little recourse but to accept the Dutch Government's demands and so on the 9th of April, 40,000 Dutch soldiers poured across the border into Flanders.

Caught off guard by the sudden intervention of the Dutch, the Walloon forces were quickly overwhelmed by the combined Fleming-Dutch force at Antwerp. Despite the skill and tenacity of the Belgian General Chazal, his men were outmatched by the Dutch force under the Prince of Orange and was quickly forced into retreat. In a matter of days, the situation in Belgium had completely reversed as the Flemings and Dutch drove the Walloons southward towards Brussels. Unable to mount a proper resistance against the approaching Orangemen, the Belgian Government was forced to abandon Brussels to the approaching Dutch army on the 13th of April. While the fall of Brussels would cause the Fleming-Dutch Army to pause for some time, many within the Dutch Government and military desired the complete reconquest of the Southern Provinces and pushed for the Army to advance south into Wallonia, which it would do on the 16th of April. Fearing a complete collapse in their positioning, the Belgian Government invoked the 1831 Treaty of London and called upon the Powers for assistance against the Netherlands.

Despite their own internal unrest and economic instability, the Kingdom of France immediately heeded the call to arms almost immediately and began moving forces towards their border with Belgium. After some delay, Prussia also began moving troops towards its border with the Low Countries, while Austria and Russia remained quiet. Given their own internal unrest and distance from the theater, their silence was generally ignored by all parties. Most surprising of all however, was Britain’s overt refusal to meaningfully assist the Belgian Government in its fight against the Netherlands.

Despite being a signer of the 1831 Treaty of London, Britain was reluctant to aid a state, which for all intents and purposes in their eyes was a French satellite. French influence in Belgium had been a cause for concern under the deposed King Otto, and many had hoped that his removal from power would bring a friendlier government to power in Brussels. Yet London would be greatly disappointed when the new Walloon dominated Government continued its turn towards France, with many prominent ministers and representatives openly clamoring for the unification of Belgium with France. Britain had also begun rapprochement with the Netherlands in recent years and it had signed various trade deals that they were hard pressed to abandon given the strong economic ties between them. While the events in the Low Countries were certainly troublesome, other matters also drew London's attention.

In Central Asia the Persian Army of Mohammad Shah Qajar had boldly crossed the border into the Emirate of Afghanistan and captured the city of Herat in less than a month, shocking British agents in the region who doubted the Persians could manage such a feat. This resurgence of Persian power in Central Asia posed a significant threat to British interests in India necessitating that more military assets to be redirected to the Subcontinent. This development in Asia also reeked of French meddling, making any semblance of cooperation between Britain and France in the Low Countries an unseemly decision for the British government. Other theaters also required London’s attention, namely the Ionian Island which were clamoring for Enosis with Greece and Ireland which was clamoring for food for its starving masses. Like the rest of Europe, Britain was also struggling from economic and political upheaval of its own which limited the state’s ability to make war and the ongoing potato famine hurt Ireland immensely leading to constant unrest on the island. The growth of Socialism and Fourierism in Belgium also soured Westminster's opinion of the Belgian Government as these movements shared much in common with the damnable Charterist movement in Britain. As these groups held great influence over the Belgian Government's proceedings and measures an unfortunate correlation between the two grew as a result in London.

Nevertheless, Britain was bound by treaty to aid the Belgians should their territorial integrity be violated by any power, be it a friend or a foe. To that end, they would dispatch several ships of the Western Squadron of the Royal Navy to patrol the waters off Belgium’s coast, interdicting any Dutch vessels found in their waters. While this was deemed unsatisfactory to the embattled Belgian Government, Britain remained unconcerned with the Walloon complaints as they had technically fulfilled the terms of the treaty despite doing little to actually aid the Belgians on the ground.

With Britain ostensibly in the war and a French army some 84,000 strong under the command of the veteran commander, Marshal Thomas Robert Bugeaud, duc d’Isly marching to the Walloons aid, the Flemish and Dutch began withdrawing to their defensive positions North of Brussels where they would prepare for the coming attack. Between the 18th of April and the 5th of May a handful of skirmishes and sorties would take place between rearguard units of the Dutch army and advanced units of the French Army, but before the might of the French army the Dutch force of some 45,000 men stood little chance. Over the course of two weeks, the Dutch and Flemings were steadily forced northward by the superior French army. Making matters worse were a series of reports on the movement of a 63,000 strong Prussian army under the command of the Prince of Prussia, that was marching on their position with great haste. However, unbeknownst to both sides, Prince Wilhelm of Prussia had no intention of aiding the French and their Walloon allies. On the 6th of May, 1848, Prussian General Moritz von Hirschfeld and the 15th Division of the Prussian 1st Army opened fire on elements of the French army North of Liege revealing their entrance into the Second Belgian Revolution alongside the Dutch and Flemings.

Next Time: The Fire Spreads

[1] Around the time of the 1848 Revolutions in OTL, Karl Marx was indeed active in and around Brussels.

[2] Technically, Brouckère and Van de Weyer were born in French occupied Flanders during the Napoleonic Wars, but as noblemen from French speaking households they held strong affinities to France and the Walloons that would shape their politics.

[3] Due to increased tension between Britain and France, and by virtue Britain and Belgium, the Dutch have managed to avoid completely abandoning their claims to Belgium which has helped the Orangist movement in Flanders ITTL.

Last edited:

It's time for some prußens gloria

Gian

Banned

Hmmm...

So with the Franco-Prussian War starting three decades early, any chance if Austria decides to join with the French? And if so, might Piedmont-Sardinia decide to join with the Prussians and Dutch against both France and Austria (the former to gain Corsica, the latter Lombardy-Venetia)?

Really makes you think...

So with the Franco-Prussian War starting three decades early, any chance if Austria decides to join with the French? And if so, might Piedmont-Sardinia decide to join with the Prussians and Dutch against both France and Austria (the former to gain Corsica, the latter Lombardy-Venetia)?

Really makes you think...

This is 1848, Bismarck has just joined the Prussian Legislature. He is nowhere near high office yet.Your forgetting about one thing Bismark and he has already gathered some amazing generals and I find it in realistic that Bismark would allowed Germany to be dragged into a war like this

Oh yah your right I believe though that he still had some influence and did some stuff like form a peasant army and other stuff like ThatThis is 1848, Bismarck has just joined the Prussian Legislature. He is nowhere near high office yet.

the Kingdom of France immediately heeded the call to arms almost immediately

Immediately, you say?

But this is an exciting update. Considering Prussia's state in 1847 I actually believe they may pull through and defeat the French with the Dutch help. But to be honest, I find French victory more likely. France isn't lacking in talented generals or war-making potential compared to Prussia in 1847. And Prussia hasn't removed Austria as a threat. If Austria intercedes on the French side, I can see Prussia going down like 1806. But a major war between powers breaking out in 1847 could literally mean a French Republic and German Republic happening and Hungary freeing itself.

If the French and Germans both establish republics and become allies that would make me so happy. Even if Napoleon II is the president of the French Second Republic.

EDIT: Imagine...

Let's just say that the Austrian will be preoccupied for some time with events closer to home and Sardinia-Piedmont will likely play some part in that.Hmmm...

So with the Franco-Prussian War starting three decades early, any chance if Austria decides to join with the French? And if so, might Piedmont-Sardinia decide to join with the Prussians and Dutch against both France and Austria (the former to gain Corsica, the latter Lombardy-Venetia)?

Really makes you think...

On paper, probably not. France is still the premier land power in Europe with massive armies in the hundreds of thousands, superb generals, and excellent weapons and tactics. Prussia on the otherhand, has not undergone the various reforms that made them into the great military power they were in the 1860's and 1870's yet. They do have many of the great military officers and political thinkers like Bismarck, Roon, and von Hirschfeld, but they haven't risen to their OTL heights just yet. France will have some issues coming up that mitigate their success on the field of battle however.Another question being, is Prussia on the same level as France militarily ?

Your forgetting about one thing Bismark and he has already gathered some amazing generals and I find it in realistic that Bismark would allowed Germany to be dragged into a war like this

While Otto von Bismarck already has a reputation as a stalwart Royalist and superb speaker, he isn't exactly the most influential Prussian politician in late 1847/early 1848. I'll reveal Prussia's reason for entering the war in short order, but the resurgence of France in the Low Countries, or at least the appearance of it is a very terrifying prospect for Prussia and many other states in Europe so soon after the Napoleonic Wars.Oh yah your right I believe though that he still had some influence and did some stuff like form a peasant army and other stuff like That

Well the fighting between the Flemings and the Walloons started in December 1847 and France officially joined in favor of the Walloons in late April 1848, so the French had about 5 months to prepare for war.Immediately, you say?

But this is an exciting update. Considering Prussia's state in 1847 I actually believe they may pull through and defeat the French with the Dutch help. But to be honest, I find French victory more likely. France isn't lacking in talented generals or war-making potential compared to Prussia in 1847. And Prussia hasn't removed Austria as a threat. If Austria intercedes on the French side, I can see Prussia going down like 1806. But a major war between powers breaking out in 1847 could literally mean a French Republic and German Republic happening and Hungary freeing itself.

If the French and Germans both establish republics and become allies that would make me so happy. Even if Napoleon II is the president of the French Second Republic.

EDIT: Imagine...

A French Republic, a German Republic, and an independent Hungary you say?

Still waiting on mega-Luxemburg to unite germany and hulk-smash it's enemies into oblivion

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan League

Share: